Constructing (national) patrimony:

medieval monuments in comparative histories of architecture in Central

Europe 1890/1900–1920/30

Abstract

History of art – and history of architecture in particular – is inseparably connected with images, reproductions as well as representations. In comparing fragments and epochal characteristics, the art historian is forced to use visualisations, medial translations, regarding size, space and Multiperspectivity.

From the 19th century onwards, history of architecture developed into a scientific field playing an important role in processes of national identity formation. European countries like Poland and the Czech Republic struggled under foreign cultural, political and scientific domination in the 19th and 20th century. Particularly for this reason, national identity fulfilled a significant cultural and social function: conveying a specific ‘Polish’ or ‘Czech’ history, literature, art or architecture could compensate for the lack of national sovereignty. Medieval monuments – understood as visible documents of national history – formed a canon of national heritage or ‘patrimony’ as Françoise Choay calls it. In the selected comparative histories of architecture, in my interpretation ‘imaginary museums’, this visual canon materialises.

Most recent studies of illustrated art historical volumes published in the 19th century show that strategies of visualisation, selection and descriptions strongly influenced the discourse on architectural history and the definition of national heritage. However, the majority of those concentrate on German, French and Italian volumes. It is therefore important, to widen the scope of the investigation, for instance with regard to the Polish and Czech historiographies, in order to understand the construction of patrimony in a Central European context. The end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century is furthermore characterized by a

medial and institutional turn: manual reproductive printing techniques were replaced by photography, while history of art and architecture were increasingly institutionalized thereby strengthening their position within the academic community as ‘respectable’ scientific disciplines. This change resulted in ruptures, deviations and contingencies regarding strategies of visualisation, education and scientific methodology.

This research complements the current scientific debate on historiography of medieval architecture during the early 20th century. Furthermore, in expanding the investigated objects and analysing small aspects of this complex, pan-European context, the formation of scientific, cultural and visual knowledge can be revised.

Understanding these processes will also illuminate today’s challenges of (re)forming an adequate and justifiable canon for art history regarding post-colonial studies and transcultural, intercontinental, global art histories. Moreover, one of the main art historical tasks is to name, analyse and hence preserve art. Thus, the search for adequate and contemporary solutions to convey knowledge about art continues – not least in digital media.

Art historical discourse – Central Europe – patrimony – national identity – medieval architecture – canon – visualization – translation – comparative histories of architecture – illustrated volumes – architectural models

Introduction

„Die Wissenschaften sprechen nicht von der Welt. Sie konstruieren künstliche Repräsentationen, die sich immer weiter von der Welt zu entfernen scheinen und die sie dennoch näher bringen.“[1]

Every science, as quoted above, is necessarily prompted to use suitable representations to approach the world. However, every transfer between media creates (new) knowledge. This knowledge is dynamic, variable and shaped by contexts, previous knowledge, experience and perception habits. According to Bruno Latour, images are samples of those traces.[2] The dependence on standardised objects for scientific generalisations or comparisons already appears in the beginning of the 19th century, when scholars began to emphasise their ‘moral objectivity’[3]. In order to fulfil this new virtue, illustrated volumes were and still are used to standardise the investigated object eliminating peculiarities. Images created for a scientific purpose like this have a certain autonomy in the discourse, particularly in art history.

Such illustrated volumes on medieval architecture published in the beginning of the 20th century are at the core of my research interest and upcoming PhD project.

The number of art historical volumes had significantly increased since the end of the 18th century[4] – however, the needs and requirements of the addressed scientific society had changed since the first decades, regarding percipients’ demands, the scientific discourse and the technical possibilities of reproduction. The chosen period on the one hand allows to consider a rich diversity of publications. After all, the choice of a specific reproduction or printing technique determines the representation of the architectural body and is therefore an essential part of a well-considered visual construction. On the other hand, the institutionalisation of architectural history in academies of art, polytechnics and universities was underway in many European countries.

From the 19th century onwards comparative volumes tend to present architectural monuments as examples of a specific style and art historical epoch or as an expression of national belonging. This understanding of artworks as historical documents can also be found in conceptions of museums and collections of architectural models of the time: Medieval monuments were and are valued as resources for (re)defining national identity.[5] Images of those national monuments displayed in different media, therefore, shaped and are still shaping the discourse of architectural history in a significant way – they influence our understanding of European heritage and the corpus of art history.

Thus, analysing these images will cast new light on strategies of visualisation and the process of constructing national patrimony (re)presented in, by and through media, precisely architectural models and illustrated volumes.

The visual translations in books seek to solve the dilemma of representing the architectural body in a two-dimensional medium, in a manageable size for a scientific purpose or within an educational context, for example in prints or photography, but also in exhibitions. Hence, it is crucial to enquire, how the authors (curators in museums and artists, e.g. photographers, engravers, draftsmen or sculptors) address the problem of representation and which techniques of translation they utilise to transfer the object to another medium of communication. Furthermore, the image is embedded into a specific line of argument. In understanding this medial transfer as translation, the productivity of this process is highlighted: in translating the object, the author (curator and artist) creates a new form of communication shaped according to their interpretation. Therefore, all visual translations are connected by an epistemic potential of representation. This potential is visible as artworks per se, such as printed reproductions of monuments, not only visualise knowledge but create meaning themselves, for instance, in favour of a specific narration. As a consequence, translated artworks become places of experience and interaction between image and observer.

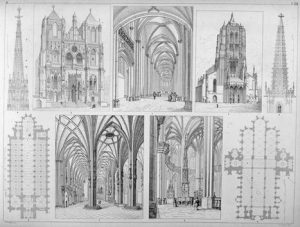

Current studies on illustrated and comparative architectural histories, that will be discussed below, as well as my own research so far identify the following, briefly summarised visualisation methods: the architectural monument is frequently represented in ground-plans, elevations and interior views arranged on a single plate (or page) and compared to other representations of similar monuments or fragments. In other cases, some details are presented in a rather artistic way, hereby following for example rules of symmetry or ornamentation. Visual translations of architectural monuments clearly adhere to (fundamental aesthetic) principles such as homogenisation and conformity, thus allowing the percipient to compare heterogeneous objects in a more or less rationalised and domesticated form. These are fragmented, isolated from their original contexts and arranged in complex compositions – an approach, which not only makes the objects suitable for stylistic comparisons, but also justifies their use as authentic documents of a specific, often ideologically shaped narrative. Those visual translations are thus imminent samples of a comparative architectural history and lie at the core of the scientific discourse.

The term ‘imaginary museum’ (André Malraux “Musée imaginaire”, 1952) provides the opportunity to understand the whole process of shaping comparative history and constructing patrimony as a creative and productive technique. Consequently, I consider illustrated volumes to be imaginary museums, since they convey knowledge following the same objectives as museums: selecting, arranging and translating objects according to a specific intention.

“Le choix des oeuvres étant ordonné par l’idée même de Musée imaginaire, chacune est choisie en fonction de son propre style.”[6]

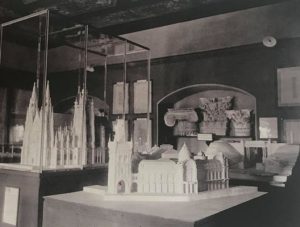

One can assume that a similar development took place within the area of production and use of architectural models, which this project also understands as representations of patrimony and as resources for constructing and defining national identity. They represent another medium of the coeval scientific discourse. Nevertheless, the latter will be considered a special case given the unfavourable preservation of many models and the frequent lack of information about the model itself, its use, or provenance.

Thesis

The planned PhD project seeks to provide answers to the question, how images of monuments were constructed in the German-, Polish- and Czech-speaking discourses in the early 20th century, how they changed (or did not change) since the 19th century and how they contributed to a visual construction of national heritage and patrimony.

Poland did not gain sovereignty until 1916. Bohemia and Moravia were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the foundation of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Correspondingly, national heritage played an important role in movements of national revival and resistance[7], cultural debates and the discourse about art history in both countries. In addition, the dominance of the German-speaking scientific community in the mid-19th century lead not only to countermovements, but also to an emergence of productive exchanges. In all three contexts the cultural and hence also scientific situation changed within the processes of institutionalisation of art history and the developing of (cultural, social, political) independence. Correspondingly, the objectives of scientific art history developped.

„Wir konservieren ein Denkmal nicht, weil wir es für schön halten, sondern weil es ein Stück unseres nationalen Daseins ist.“[8]

This research will show that architecture is understood as an inclusive art form (integrierende Kunstform[9]) and symbol of national identity. Historical monuments became understood as national heritage and required grant-aided measures to preserve their form and to convey their meaning. The newly emerging art historical disciplines approach was ambivalent: On the one hand, art history was narrated as a linear stylistic development, on the other hand, understanding formal variations as national characteristics of art isolated countries, histories and people. The context of art historical discourse indicates that this ambivalence clearly refers to integrations, interconnections and interweavings between nations. Correspondingly, Georg Dehio and Franz Winter published their ‘Kunstgeschichte in Bildern’ in 1902 with images of monuments and sculpture arranged according to separate nations, but without emphasising the superiority of the German style.

Tabl. II, 59: Gotische Baukunst Deutschland. Aus: Dehio, Georg; Winter, Franz (1902): Kunstgeschichte in Bildern. Mittelalter. Leipzig.

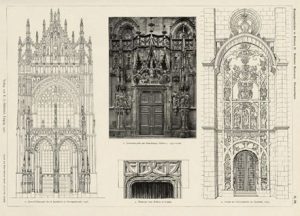

This approach obviously differs from the Polish- and Czech-speaking chosen examples by Jan Sas Zubrzycki (1907-1913) and Ferdinand Lehner (1903, 1905) who already in the title of the volumes state their objective to describe a Polish or Czech art history only.[10]

Within my analysis, I focus on the following thesis: The German-speaking scientific community in the beginning of the 20th century tries to interpret art history from a scientific and objective perspective using national styles as a formal characteristic. Nevertheless, the canon of chosen monuments clearly shows a focus on German, French or Italian architecture and is not reflected in the discourse. In the contrary, the formation of a western focused discourse is noticed in Central Europe. The Polish-speaking discussion is characterised by the attempt to integrate Polish art history, especially medieval monuments, into the Pan-European scientific canon. Czech-speaking publications however, exert to establish an own, ‘Czech’ discourse for a Czech audience, independent from the contemporary German-speaking discussion or even against it. The volumes treat Czech monuments, pointing out Pan-European or Slavic interconnections only to characterise the uniqueness of Czech art.

In comparing the three stated perspectives on architectural history, the influence of the current political or institutional situation and cultural or personal experiences can be retraced. In addition, the focus on medieval architecture in my research reflects the coeval understanding of medieval art as central and important referring point for national identity and collective historical memory.

The PhD project will furthermore show that the problem of an objective and justifiable art historical canon has not been resolved until today, since we are deeply indebted in the medial and institutional construction of a canon and heritage through (these) illustrated art histories. Art historical and cultural knowledge has been visually constructed in forms of imaginary museums, long before André Malraux published his ‘musée imaginaire’ in 1947. Generally speaking, imaginary museums reflect the method of comparative looking at art (Vergleichendes Sehen), fundamental in practising or teaching art history since the beginnings of the discipline until today. On a meta-level, I argue that the construction of those binary comparisons, the formation of an art historical canon, is rarely discussed. The current discourse on the history of art history and today’s corpus of architectural history demonstrate the continuity of Western-European dominance.

Nevertheless, attempts to convey art historical knowledge in a digital world may on the one hand change this limitation of discourse and show, on the other hand, the importance of creating ‘imaginary museums’ whilst visually translating our knowledge into digital media.

State of research and methodological approach

In the following I will briefly summarise the relevant research concerning this project to expound my own approach afterwards. The summery is thematically ordered.

Medieval architecture in the art history of the 19th and 20th centuries

Academic works focusing on the historiography of art and architectural history, i.a. by Wolfgang Cortjaens and Karsten Heck (2014), Matteo Burioni (2016) or Klaus Jan Philipp (1998), provide important overviews and methodological approaches to cope with a historiographic task. In particular, the volume ‘Bilderlust und Lesefrüchte. Das illustrierte Kunstbuch von 1750 bis 1920‘ published in 2005 by Katharina Krause, Klaus Niehr and Eva-Maria Hanebutt-Benz or Hubert Lochers ‚Kunstgeschichte als historische Theorie der Kunst 1750-1950‘ (2010) develop important categories and terms to understand the history of art history in the chosen period. Klaus Niehr distinguishes here between monographic and comparative histories of architecture. This differentiation is crucial for my own corpus of investigation and helped organising the huge quantity of possible examples.

Following Hubert Locher (2010) in understanding illustrated volumes as ‘imaginary museums’, provides the possibility to emphasise the relation between different media. In addition, the below listed research on the history and concepts of exhibitions about medieval architecture can be used to understand similar approaches in printed books of the same time. Until the 20th century exhibitions have been characterized by chronological arrangement, stylistic fragments and the presentation of imaginative reconstructions of monuments or epochs. Those fragments represent not only a typical style, but they also function as representatives for the (whole) original art work. Isolated from their former context they become elements of fictional monuments according to the exhibited narration. Consequently, scholars like Markus Thome (2015) not only analyse the form of representation, but also the context, that shapes and constructs the ‘narrative superstructure’ (narrativer Überbau). In the last two decades, the history of the medieval object within the context of 19th century museums has been addressed by many scholars, such as by Wolfgang Brückle et al. (2015) or Bernward Daneke et.al. (1977).

Similarly, the reception of medieval art in general is a priority in studies by Daniela Mondini (i.a. 2006, 2014), Matthias Noell (i.a. 2006), Klaus Niehr (i.a. 1999) or Klaus Jan Philipp (i.a. 2006) and others. All listed scholars stress the relation between media and art history, or the science of history in general.

The use of art works as authentic and historical documents has been broadly discussed since the iconic turn. Studies focusing on reader-response criticism show that representation methods and relations between pictorial elements within the image construct authenticity, historicity and a scientific form. The understanding of visual translations of monuments as authentic ‘stylistic samples’ (Stilproben[11]) for the history of architecture is discussed by Daniela Mondini (i.a. 2006), Matthias Noell (i.a. 2006) or Markus Thome (2015). Klaus Niehr (2006) is furthermore questioning the repercussion those images and receptions of medieval architecture have on the original objects themselves.

From the beginning of the 20th century not only (national) museums and illustrated volumes, but a broad variety of media have been used to convey an history of art.[12] In this account, I chose presentations and collections of architectural models to widen the corpus of illustrated volumes for another form of visual communication in order to retrace their relation in the coeval discourse.

The quantity of produced architectural models increases during the 19th century and is closely related to the integration of architecture in polytechnics and universities. Yet, it is rarely discussed and detected in scientific research about the history of art history.

Significantly, Werner Oechslin (2011) describes in his contribution to Wolfgang Sonne’s volume ‘Die Medien der Architektur’ the close connection between drawing and architectural model as they both convey the same information about the original object. The question of how the model is to be used, is defined by Battista Alberti and his colleagues. Everything that follows is ‘repetition’, Oechslin summarises. In contrast, the cases of use for models extended in the late 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. In accordance with the coeval discourse, architectural models became objects of scientific investigation and mediation of patrimony.

Hans Reuther and Ekhart Berckenhagen (1994) focus on the history of architectural models after 1500 until 1900. The book is followed by a catalogue of German architectural models, embodying an important starting point for my own research. The authors distinguish between models of memory (Erinnerungsmodelle) and models of reconstruction (Rekonstruktionsmodelle), imagining or conserving certain states of construction. Architectural models are very heterogeneous: some devoted to exact scales and measurements, others rather displaying narrative arrangements. Nevertheless, the potential of models is not merely limited to the presentation of an object. The reduction of complexity for example through isolating the object from its urban context or the concentration on separate elements, rather allows different possible interactions with the object itself and also with its (photographic) reproductions or its presentation. Unfortunately, the lack of further research impedes to integrate the architectural model into my own corpus of investigation. Therefore, I focus on one specific collection, the collection of architectural models in the National Technical Museum (NTM, 2015) in Prague. The NTM houses several models produced in the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, displaying medieval architecture. They also preserve archival information and photographs about exhibitions, that will help to cope with the listed challenges.

Expozice architektury ve Schwarzenberském paláci, Národni Technické Muzeum Prag – Aus: Národni Technické Muzeum. Katalog expozice Architektura, stavitelství a design. Prag. 2015, S.14.

Translational theory and the translation of art

Combining art historical studies with translational theory, shaped by the literal studies after the so called ‘translational turn’ (Bachmann-Medick, 2006) in the 1980s, facilitates to describe the process of transferring content from one medium to another not only as reproductive but rather as productive. Bachmann-Medick integrates cultural translational practices into traditional translational studies. She emphasises limits and their exceeding within translation. With this approach, she enables the use of the term ‘translation’ and its methodology to cope with complex cultural systems and their hybridity. In contrast to a holistic understanding of culture, translation functions as a method to negotiate limits and differences. Misunderstandings, ruptures, deviations and contingencies shape this process of mediation and become visible within analysis.

Lawrence Venuti (1995) describes the ‘Translator’s Invisibility’ in translated texts. Invisibility is intended to reach a higher readability or fluency and is achieved through processes of transparency like familiarisation or domestication. In contrast to the invisibility of the translator in texts, translations between media cannot be as transparent regarding the differences of communication or form they offer. Nevertheless, the translator between media tries to fulfil the same objective: transferring the object with its essential content adequately into another system of communication, whilst simultaneously taking into account the requirements of the new context.

Walter Benjamin understands translation in general as an instrument to discover the ‘truth’ and ‘essence’ (Wesen) of the object in his article “Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers” ([1923]1972). He argues that translations bring the object closer to its essential meaning by offering different perspectives on and approaches to its materiality and form. This theoretical understanding of translations contradicts his thoughts about the reproduction of art and the loss of the original’s aura.[14]

Summarising this brief overview of translational theories, considered important for my own research, the productivity and cultural impact reflected in those works will enrich my approach to the strategies of visualisation.

Constructing patrimony

The objective of my project is to analyse, how the visual translation of monuments into illustrated volumes and architectural models contributes to a construction of (national) patrimony. I am using the approach of Françoise Choay (1992) and Roland Recht (1997) to relate my analysis, understood as microhistories, to the broader context of art historical discourse, in order to retrace the medial construction and the social, cultural or political function of patrimony in comparative histories of architecture.[15]

As above mentioned, medieval monuments are an important resource for constructing national identity. Strategies of translating the objects and integrating them into a specific system of classification, refer to the coeval interaction of nationalism and art history.

„Monument et ville historique, patrimoine architectural et urbain: ces notions et leurs figures successives dispensent un éclairage privilégié sur la façon dont les sociétés occidentales on assumé leur relation avec la temporalité et construit leur identité. […] Ensuite, la construction iconique et textuelle du corpus des antiquités, classiques ainsi que nationales, permet aux sociétés occidentales de poursuivre leur double travail originel: construction du temps historique et construction d’une image de soi progressivement enrichie par des données généalogiues.“[16]

Françoise Choay analyses this double function – the construction of historical time and the construction of a self-image -, by analysing the use of and discourse on historical monuments in the pan-European society:

“Mes examples sont souvent empruntés à la France. Ils n’en demeurent pas moins examplaires: en tant qu’invention européenne, le patrimoine historique relève d’une même mentalité dans tous les pays de l’europe. Dans la mesure où il est devenu une institution planétaire, il confronte à terme tous les pays du monde aux mêmes interrogations et aux même urgences.

En un mot, je n’ai pas voulu faire de la notion de patrimoine historique et de son usage l’objet d’une enquête historique, mais le sujet d’une allégorie.”[17]

Hence, Françoise Choay in her book identifies the founding texts and figures of conservatory practice. Roland Rechts’ research on gothic patrimony and the historiography of gothic art, e.g. ‘Penser le patrimoine […]’ (1999, 2008), offers a starting point for the envisioned history of discourse and media in the Central-European context. Roland Recht argues, that the patrimonial object on the one hand is a place of memory (lieu de mémoire) and on the other hand an important tool for the historian. Within art history, both statuses are reconciled.[18] Analysing patrimony and especially its reception offers the possibility to understand their value or esteem and meaning in different times or cultural contexts, since the knowledge about objects is always shaped by the institutional context of their use. Furthermore, the anthropological function of national ‘patrimony’ is crucial according to both scholars:

„Das Denkmal schützt diejenigen, die es errichten, und die anderen, die seine Botschaft empfangen, vor den traumatischen Momenten der Existenz und gibt ihnen Sicherheit. […] Das Denkmal ist der Versuch, die Angst vor dem Tod und dem Verschwinden im Nichts zu beschwichtigen.“[19]

Processes of constructing national heritage thus not only depend on social, political and cultural circumstances but influence the perception of history, in the past and present. The role of architectural patrimony in the construction, maintenance and development of (national) identity is essential.

The obstacles or taboos that reserved the enjoyment of art works to insiders, elites and privileged could be overcome, argues Françoise Choay[20], through technological innovations, extended media and the development of the imaginary museum open to all.

Polish-, Czech- and German-speaking volumes offer an interesting medial variety of forms of patrimony and subsequent practices of their use. The understanding of patrimony in the beginning of the 20th century includes furthermore infringements and differences. The chosen corpus of volumes and objects therefore provides a rich source for microhistorical studies on scientific historiography and discourse history, that can be related to a general coeval art historical discourse.

Central European comparative histories of architecture

In 2016 the international conference ‘Nationalismus als Ressource? Konsens und Dissens in der europäischen Nach- und Neogotik des 19. Jahrhunderts’ at the institute for art history in Bern, amongst others, revealed the lack of knowledge about and research on Central-European art history. The conference included two contributions on Czech architecture from the end of the 19th century and one lecture on Transylvanian history of architecture.

However, most of the studies on illustrated volumes concentrate on examples published in Germany, France or other Western European countries. For this reason, the corpus of research for this PhD project will be widened to Polish-speaking and Czech-speaking volumes.

On a meta-level, the hereinafter named research demonstrates that the discourse about Central European art history, interconnections and (national) differences is a subject of current studies. Yet, this research is not represented as it should be in today’s German-speaking debate. It is therefore urgent to integrate and discuss studies about Central European art history, once investigating pan-European comparative histories of architecture.

The chosen period of time spans the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, when former Poland was still divided and shared by the Russian, Prussian and the Austro-Hungarian regimes, while Czech-speaking lands were under Habsburg rule, up until the creation of the independent states of Poland in 1916 and Czechoslovakia in 1918. Germany was united in 1871 and reorganised after World War I as the newly formed Weimar Republic in 1918. As exemplified earlier, the writing of art history played a significant role in (re)constructing national identity, accompanying those changes: First, with the aim to unite the Germans, or to remember and maintain Polish and Czech culture under foreign sovereignty, later to justify the new states. The forming of Czechoslovakia constitutes another challenge: the integration of Slovak art and culture into the Czech history and art history.

Marta Filipovas thesis ‘The construction of national identity in the historiograhy of czech art’ (2008) provides an important outline of the coeval discourse on Czech national art history. Besides this research, the studies by Rudolf Chadraba et. al. (1986), Petr Wittlich (1992) and Jiři Kroupa (1996) remain important reference resources regardless of their frequent lack of apprehension of national bias. Furthermore, i.a. Milena Bartlova (2013, 2012), Marta Filipova (2013a+b) and Jindrich Vybiral (2006) examined the writing and forming of Czech art history. They focus on the construction of national identity, international relations or the coeval artistic community. In addition, Matthew Rampley (2013) analyses the influence and discourse of the so-called Vienna School of Art History, that was established at the beginning of the 20th century at the University of Vienna. He aswell edited the compendium ‘Heritage, Ideology and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe. Contested Pasts Contested Presents’ (2012b).[21]

Critical overviews of the Polish historiography of art history are rather rare: In 1995, Jolanta Polanowska and in 1996 Adam Lubuda (ed.) expounds the writing of art history in Poland in the 18th and 19th century. Anna Brzyski (2004) offers a brief overview on the canonisation of Polish paintings in the 19th century; followed by Adam Małkiewicz (2005), who outlines the development of art history in Poland. Furthermore, scientific articles by i.a. Carolyn Guile (2013), Magdalena Kuninska (2013) and Stefan Muthesius (2013) characterise important figures in the process of writing of art history in Poland. Nevertheless, a broader critical analysis of the art historical discourse of the beginning of 20th century is lacking.

‘History of Art History in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe’ edited by Jerzy Malinowski in 2012 serves as a methodological basis for the upcoming analyses. The contributions to this compendium provide insights into microhistorical examples of the Central and South-Eastern European discourse of the time, which I aim to complement with this research.

A first overview of holdings of and research in the national libraries of Poland and the Czech Republic show, that Polish-speaking scientific volumes on art history have been published since the early 19th century. Meanwhile, in the Czech Republic, German-speaking scientists dominated the discourse on Czech national art history until the end of the 19th century. While both countries suffered under foreign dominion, their approaches to national art history were different.

As mentioned above, I follow the thesis that Polish scholars tried to integrate their knowledge and national monuments into the international discourse, whilst publishing in two or more languages and referring to foreign studies. Czech scholars, however, established an own, independent discourse on national architecture especially in contrast to the German understanding of Bohemian art history. The romantic tradition of mystifying and imagining medieval architecture (and national history) shifted at the turn of the century. Not only processes of institutionalisation influenced the discourse on Czech art, but also artist’s clubs or societies, journals and exhibitions. The relation between writing and teaching of art history with contemporary art is assumed to be close and reciprocal. A new generation of art historians, graduates from the University of Vienna and educated by Max Dvořak and other members of the ‘Vienna School’, developed more objective and rigorous methods to approach Czech art. The cosmopolitan or modernist views inspired the writing of art history in Prague, but simultaneously offended more conservative Czech scholars. The chosen illustrated volume by Ferdinand Lehner (1903, 1905) demonstrates this interesting turning point in the Czech discourse. As a pupil of Jan Erazim Vocel (1803-1871) he personifies a more conservative approach:

„His [Lehners] reading of history was influenced by his attempt to show architectural monuments as he imagined them in order to show a rich resource of ecclesiastical architecture in medieval Bohemia.“[22]

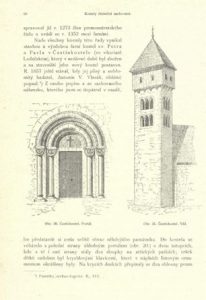

Obr. 20, Obr. 21. Aus: Lehner, Ferdinand J. (1903): Dějiny uměni naroda českeho. Prag.

Yet, the images of medieval architecture he uses are characterised by modernist methods of illustrating, translating and promoting art history as an objective science.

Wojciech Bałus (2012) argues that the institutionalisation of art history in Poland first took place in Cracow under Austrian rule, when the Commission of Art History at the Academy of Arts and Science was founded in 1873[23]. A main purpose of this institute’s activities was the inventorying of Polish monuments, the writing of Polish art history and the publication of monographic studies on Polish art works. Comparably to the Czech situation, the trained historian, Marian Sokołowski entrusted with the first chair of art history at the University in Cracow, had studied in Vienna (and Berlin).

“When writing about Polish art, he [Sokołowski] always tried to portray it as an integral part of the European legacy.”[24]

Sokołowskis attempts to depict Polish art history as characterised by the affiliation with the German-speaking discourse: In his lectures he promoted concepts by Carl Schnaase or Anton Springer, while benefitting from the liberal regime of the Habsburg Empire in Galicia. This situation contrasts the events in Prussian-ruled Poznań or the Russian-ruled Warsaw, that suffered under policies of enforced Germanisation or Russification. After the recovering of independence in 1918 (Polish) art history was (re)established in Poznań, Warsaw and Lviv. The chosen example of Polish comparative history of architecture was published in 1907 by Jan Sas Zubrzycki (1860-1935). He follows the stated objective to make an inventory of Polish architectural monuments and presents them in rather eclectic arrangements. Yet, the selected compendium aims to contribute to an international discourse by being published in Polish and French, referring to popular scholars like John Ruskin and creating an image catalogue for stylistic and formal comparisons using photography and wood prints.

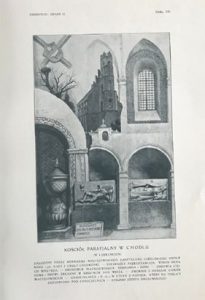

Tabl. 135: Kościół parafjalnz w Chodłu. Aus: Zubrzycki, Jan Sas (1907): Skarb architektury w Polsce = Le trésor de l’architecture en Pologne = Formenschatz der Architektur in Polen. Krakau.

Both examples of comparative histories of architecture exemplify the coeval discourse about patrimony and provide images of medieval monuments, valued as unique, stylistic examples of national art. In comparison with the German volume by Georg Dehio and Franz Winter, I aim to relate the Polish and Czech discussion about national art history with a Central European discourse on patrimony.

Producing digital heritage

Studying the discourse on art history at the beginning of the 20th century cannot be processed without reflecting on the researchers’ own scientific backgrounds and the question of how the results of the upcoming project could impact today’s thinking about art history. I am convinced that our understanding of art history and history of architecture is deeply indebted in the history of our scientific field. Institutionalising art history in the beginning of the 20th century not only led to a more systematic approach to the artwork itself, but also to the shaping of a limited canon.

“L’interprétation du synodrome patrimonial permet de mesurer l’urgence de ce choix qui, répétons-le, n’est pas incompatible avec des développements de la technique. Si nous le faisons, le patrimoine architectural et urbain de l’ère pré-industrielle trouve une fonction, irremplacable et neuve. Il nous sert d’appui pour inventer notre avenir.”[25]

The challenge art history is facing with today’s digitalisation finally bears the opportunity to reshape and rethink this canon, as Françoise Choay has been expecting art historians to do since the 1990s.

Attempts to convey art historical knowledge in a digital world may on the one hand change this limitation of discourse due to a global connection of stocks, e.g. digitalised library collections, and show on the other hand the importance of creating ‘imaginary museums’ whilst visually translating our knowledge into digital media, into a new form of knowledge.

Projects like the ‘Virtuelles Kupferstichkabinett’ or the digital experiments by the Universitäts- and Landesbibliothek Darmstadt are suggesting first approaches producing digital patrimony.[26] I would like to contribute to this current progress of art history by developing a digital, connected catalogue of objects regarding the PhD research data.

The underlying question of canon and its interpretation is approached by Hubert Locher (2012). He ascertains the lack of a critical discussion on the canon and canonical art in concepts of art history. After retracing the term ‘canon’ back to earliest European theories of art, he describes the canon as a “system of references produced in a certain cultural context”.[27] The canon therefore is influenced by individual as well as collective identity and represents the society’s values and interpretations.

Building on the above mentioned, the planned PhD thesis seeks to analyse the process of canon formation in Central European comparative histories of art. Taking into account the above listed research, the central question is therefore: how is the medieval monument visualised in comparative histories of architecture at the beginning of the 20th century? And what kind of relation do these images bear to the discourse on history of architecture in all three languages?

Consequently, I will analyse the construction of patrimony on a microhistorical level in order to relate the results to a pan-European art historical discourse.

______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Latour, Bruno (1996, 197), see as well earlier Latour, Bruno (1981).

[2] In the chapter ‘Arbeit mit Bildern: Die Umverteilung der wissenschaftlichen Intelligenz’ Bruno Latour (1996) pictures new media in the 1970s changed scientific methods of investigation and the forming of knowledge.

[3] Daston/Galison (2002, 88). The forming of knowledge and the circulation of images, especially photographs, is reflected in Peter Geimers anthology ‘Ordnungen der Sichtbarkeit’ (2002). Another interesting approach can be found in Martina Heßler’s book ‘Konstruierte Sichtbarkeiten’ (2006).

[4] Important works of this early period have been produced by Bernhard Fischer von Erlach (1721), Julien-David Leroy (1764), Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand/ Jacques-Guillaume Legrand (1800), Louis-Francois Cassas (1806), John Britton (1807-1826) und Séroux d’Agincourt ([1810-] 1823). Followed by Georg Gottfried Kallenbach (1847, 1850), Franz Kugler (1841ff.) and Ernst Guhl/Johann Caspar (1851), Karl Schnaase (1850, 1854, 1856) or Wilhelm Lübke (1855) just to name some of the most important works.

[5] Medieval monuments still are central to the understanding of national identity like the reactions to the fire in Notre Dame de Paris showed just recently: “Notre-Dame de Paris en proie aux flammes. Émotion de toute une nation. Pensée pour tous les catholiques et pour tous les Français. Comme tous nos compatriotes, je suis triste ce soir de voir brûler cette part de nous.” (Emmanuel Macron, 15.04.2019, Twitter), „Es tut weh, diese schrecklichen Bilder der brennenden #NotreDame zu sehen. #NotreDame ist ein Symbol Frankreichs und unserer europäischen Kultur. Mit unseren Gedanken sind wir bei den französischen Freunden. #Paris“ (Steffen Seibert, Regierungssprecher, 15.04.2019, Twitter), „Notre-Dame de Paris est Notre-Dame de toute l’Europe. We are all with Paris today. “ (Donald Tusk, 15.04.2019, Twitter).

[6] Malraux, André (1952 [1947-1950]/773).

[7] The Polish resistance movement against the foreign occupation peeked in 1830/1831 with the November Uprising and in 1863/1864 with the January Uprising. This movement was accompanied by the attempt to preserve and cultivate the Polish culture. The Czech National Revival was a cultural movement which took place in the Czech lands during the 18th and 19th centuries. The purpose of this movement was to revive the Czech language, culture and national identity.

[8] Dehio, Georg (1905/11).

[9] Locher, Hubert (2010, 73). The term ‘inclusive art form’ describes the new political function architecture receives in the 19th century debates. Architecture gets integrated into the political debate, conveying national identity, while simultaneously political debate is integrated into art history.

[10] See illustration n.1-3.

[11] Thome, Markus (2015).

[12] Besides illustrated volumes, exhibitions and architectural models, journals, scientific and artistic societies or lectures can be named.

[13] i.a. Clausen, Christina (2016): Designing Cultural Memory: The Medieval Cathedral as a ‘Monument to History’ in Nineteenth-Century Painting, in: What’s the Use? Constellations of Art, History, and Knowledge, A Critical Reader, hrsg. von Nick Aikens, Thomas Lange, Jorinde Seijdel, Steven ten Thije, Amsterdam 2016, S. 92-110.

[14] Benjamin, Walter (2012 [1939]).

[15] Using the term microhistory I refer to corresponding research in cultural studies and historical science, i.a.: Ginzburg, Carlo (1993): Mikro-Historie. Zwei oder drei Dinge, die ich von ihr weiß. In: Historische Anthropologie. Band 1, 1993. S. 169–192 or Hiebl, Ewald; Langthaler, Ernst (Hrsg., 2012): Im Kleinen das Große suchen: Mikrogeschichte in Theorie und Praxis. Innsbruck, Wien, Bozen.

[16] Choay, Françoise (1992/152).

[17] Choay, Françoise (1992/24).

[18] The abovementioned term ‘inclusive art form’ used by Hubert Locher reflects this understanding.

[19] [The German translation differs in small details from the original French version and has been published in close cooperation with F. Choay herself. Therefore, I use the German text as a revised original] Choay, Françoise (1997/15).

[20] Françoise Choay (1992/173).

[21] Max Dvořak is known for playing an important role in this development.

[22] Filipova, Marta (2008/81).

[23] History of art already was a subject in lectures at universities in Lviv, Cracow and Warsaw earlier. See various articles in Malinowski (2012).

[24] Bałus, Wojciech (2012/439).

[25] Choay, Françoise (1992/190).

[26] Virtuelles Kupferstichkabinett: http://www.virtuelles-kupferstichkabinett.de/de/ ; Digital collections of the Universitäts- and Landesbibliothek Darmstadt, https://www.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/ulb/digitalisierungszentrum/digitale_sammlungen/digitale_sammlungen_1.de.jsp

[27] Locher, Hubert (2012/4).

Bibliography (in selection)

Primary literature: comparative history of architecture in Central Europe, 1850-1935 (in distinct selection)

Bergner, Heinrich (1906): Handbuch der Bürgerlichen Kunstaltertumer in Deutschland.Leipzig.

Bersohn, Mathias (1895, 1903): Kilka słów o dawniejszych bożnicach drewnianych w Polsce. Heft 1 und 2. Krakau.

Birnbaum, V; Cibulka, Jos.; Matejcek, Ant; Pecirka, Jar.; Stech, V.V. (1931): Dějepis výtvarného umění v Čechách. Prag.

Birnbaum, Vojtech (1924): Romanska Renesance koncem stredoveku. Prag.

Dehio, Georg (1930): Geschichte der deutschen Kunst. Berlin.

Dehio, Georg; Winter, Franz (1902): Kunstgeschichte in Bildern. Leipzig.

Dohme, Robert (1887): Geschichte der deutschen Baukunst. Berlin.

Forst-Battaglia, O. (1931): Polnische Kunstgeschichte 1927-1929. In: Jahrbücher für Kultur und Geschichte der Slaven.

Förster, Ernst (1855): Denkmale deutscher Baukunst, Bildnerei und Malerei von Einfuhrung des Christentums bis auf die neueste Zeit. Leipzig.

Frankl, Paul (1926): Die Frühmittelalterliche und romanische Baukunst. Potsdam.

Gerstenberg, Kurt (1913): Deutsche Sondergotik. Eine Untersuchung über das Wesen der deutschen Baukunst im späten Mittelalter. München.

Grueber, Bernhard (1871): Die Hauptperioden der mittelalterlichen Kunstentwicklung in Böhmen, Mähren, Schlesien und den angrenzenden Gebieten. Prag.

Grueber, Bernhard (1871): Die Kunst des Mittelalters in Böhmen. Wien.

Guhl, Ernst; Caspar, Joseph (1851): Denkmäler der Kunst zur Ubersicht ihres Entwicklungs-Ganges von den ersten künstlerischen Versuchen bis zu den Standpunkten der Gegenwart (Band 1). Denkmäler der Alten Kunst. Begonnen von Prof. A. Voit in Munchen. Stuttgart: Verlag von Ebner & Seubert.

Hellrich, Josef; Kandler, Wilhelm; Mikowec, Ferdinand B. (1860, 1865): Alterthümer und Denkwürdigkeiten Böhmens. Zwei Bände. Prag.

Hellrich, Josef; Kandler, Wilhelm; Mikowec, Ferdinand B. (1860, 1865): Starožitnosti a Památky země České. Zwei Bände. Prag.

Hinz, Jan (1889): Szkice architektoniczne krajowych dzieł sztuki. Warschau.

Höver, Otto (1923): Vergleichende Architekturgeschichte. München.

Knötel, Paul (1921): Kunst in Oberschlesien: ein Wegweise für Oberschlesiens Volk und Jugend. Kattowitz.

Kozicki, Władysław (1920): Sztuka polska: (zarys rozwoju polskiego malarstwa i rzezby = l’art polonais. Warschau.

Kraus, Franz Xaver (1897): Geschichte der christlichen Kunst. Freiburg.

Kugler, Franz (1842 (2. Aufl. 1848, umgearbeitet 1856, 1859): Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte. Stuttgart.

Kugler, Franz (1853-1854): Kleine Schriften und Studien zur Kunstgeschichte. 3 Bände. Stuttgart.

Kugler, Franz (1856, 1858, 1859): Geschichte der Baukunst. Stuttgart: Verlag von Ebner & Seubert.

Kunsthistorische Bilderbogen (1886). Leipzig: E. A. Seemann Verlag.

Lehner, Ferdinand J. (1903-1905): Dějiny uměni naroda českeho. Prag.

Lelewel, Joachim (1851): Polska wieków średnich. Lwow.

Lityński, Michał; Nittman, Karol Jan; Spamer, Adolf; Kubala, Ludwik (1900): Illustrowana historya średniowieczna. T. 1, Od wędrówki narodów aż do wypraw krzyżowych. Wien.

Lübke, Wilhelm (1875 [1855]): Geschichte der Architektur von den ältesten Zeiten bis zur Gegenwart. 782 Abb. Leipzig: E. A. Seemann Verlag.

Luchs, Hermann (1859): Romanische und gotische Stilproben aus Breslau und Trebnitz: eine kurze Anleitung zur Kenntniss der bildenden Künste des Mittelalterst; zunächst Schlesien. Breslau.

Łusczkiewicz, Władysław (1889): Studya nad zabytkami architektury romańskiej w Polsce. Zwierzyniec – Prandocin – Konin – Staremiasto – Kazimierz – Czerwińsk. Krakau.

Lutsch, Hans (1886): Verzeichnis der Kunstdenkmaeler der Provinz Schlesien (1886-1903).

Lutsch, Hans (1903): Bilderwerk Schlesischer Kunstdenkmäler, Drei Mappen – ein Textband – Mappe I Mittelalter. Breslau.

Madl, Karel (1897): Soupis památek historických a uměleckých v království Českém od pravěku do počátku XIX. století. Prag.

Madl, Karel (1898): Topographie der historischen und Kunst-Denkmale im Königreiche Böhmen von der Urzeit bis zum Anfange des XIX. Jahrhunderts. Prag.

Matthaei, Adelbert (1899): Deutsche Baukunst im Mittelalter. Leipzig.

Mertens, Franz (1850): Deutsche Baukunst des Mittelalters. Berlin.

Noakowski, Stanisław (1920): Architektura Polska: szkice kompozycyjne. Warschau.

Orda, Napoleon (1875): Album widoków gubernij Grodyieńskiej, Wileńskiej, Mińskiej, Kowieńskiej, Wołyńskiej, podolskiej iKijowskiej w dwóch Seryach yawierających 80 widoków, pryedstawiających miejsca historyczne y czasów wojen tureckich, tatarskich, krzyżackich i kozackich, oraz mogiła perypiatychy, Zamku Mamaja w Bukach etc. 4 Bände (mehrere Serien). Warschau.

Orda, Napoleon (1875): Album widoków przedstawienych miejsca historycyne Księstwa poynańskiego i prus zachodni. Warschau

Orda, Napoleon (1875): Album widoków przedstawienych miejsca historycyne Królestwa Galicyi i yiem krakowskich. Warschau.

Orda, Napoleon (1875): Album widoków przedstawienych miejsca historycyne od początku Chrześciańska w tym kraju oray stare ruiny zamków obronnych w guberniach warszawskie, kaliskiej, piotrkowskiej i kieleckiej. Warschau.

Ostendorf, Friedrich (1922): Die Deutsche Baukunst im Mittelalter. Berlin.

Passavant, Johann David (1856): Ueber die mittelalterliche Kunst in Böhmen und Mähren. In: Zeitschrift für christliche Archäologie und Kunst (1), S. 241–249.

Plenkiewicz, Roman (1903): Losy naszych zabytków architektonicznych. Warschau.

Probst, Otto Ferdinand (1900): Breslaus malerische Architekturen. Breslau.

Przezdziecki, Aleksander; Rastawiecki, Edward (1855-1858): Wzory sztuki sredniowieznej. 3 Bände. Warschau.

Romberg, J. Andreas; Steger, Friedrich (1841, 1842, 1850): Geschichte der Baukunst von den altesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. 3 Bande. Berlin.

Schnaase, Karl (1850, 1854, 1856): Geschichte der bildenden Künste im Mittelalter. Düsseldorf.

Schoenberger, Guido (1928): Das Mittelalter. Vorgeschichte und Entfaltung. Leipzig, Berlin.

Słupski, Zygmunt Swiatopełk (1900): Szkic z dziejów sztuki naszej. Posen.

Slupski, Zygmunt Świątopełk (1917): Album naszych zabytków. Posen.

Sobieszczański, F. M. (1847, 1849): Wiadomości historyczne o sztukach pięknych w dawnej Polsce. 2 Bände. Warschau.

Sokołowksi, Marian (1906): Dwa gotycyzmy: wileński i krakowski w architekturze i złotnictwie i zródła ich znamion charakterystycznych. Krakau.

Springer, Anton (1895, 1904): Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte. Leipzig.

Springer, Elfriede (1932): Niederschlesische Kunstdenkmäler.

Springer, Elfriede (1934): Schlesische Kunstdenkmaeler: Fortsetzung der ‚Niederschlesischen Kunstdenkmäler‘.

Steffen, Hugo (1908): Malerische deutsche Bauten vergangener Zeit. München.

Tomkowicz, Stanisław (1903): Style w architekturze kościelnej (szczególnie w byłej Polsce). Warschau.

Wirth, Zdeněk (1926): Československé umění. Prag.

Wirth, Zdeněk; Stenc, Jan (1913): Umělecké poklady Čech: sbírka význačných děl výtvarného umění v Čechách od nejstarších dob do konce XIX. stol.. Prag.

Wocel, Jan Erasmus (1847): Byzantinsky kostel ve vsi Svatem Jakubě. In: Časopis Českého Museum (21), S. 211–228.

Wocel, Jan Erasmus (1857): Die romanischen Kirchen zu Zaboř und St. Jakob in Bohmen. In: Mittheilungen der kaiserl. Königl. Central-Commission zur Erforschung und Erhaltung der Baudenkmale II (II), 116-119, 155-161.

Wocel, Jan Erasmus (1857): Kostely romanskeho slohu v Čechach. In: Památky archaeologické a místopisné (2), S. 118–124.

Wocel, Jan Erasmus (1863): Die Baudenkmale zu Mühlhausen in Böhmen. In: Mittheilungen der kaiserl. Königl. Central-Commission zur Erforschung und Erhaltung der Baudenkmale II (8), 11-16, 36-46.

Wocel, Joh. Erasmus (1852): Vyvinování křesťanského umění a nejstarší památky jeho zvláště v Čechách. Prag.

Zabierzowski, Aleksander (1868): Szkice architektoniczne: zbiór pomysłów architektonicznych w rozmaitym rodzaju mających na celu przyozdobienie wsi i okolic miast a mianowicie: wille, domy letnie, altany, oranżerye, ogrodzenia, ozdoby budowli wewnętrznych i zewnętrznych, mostki ogrodowe itp.. Warschau.

Zubrzycki, Jan Sas (1907): Skarb architektury w Polsce = Le trésor de l’architecture en Pologne = Formenschatz der Architektur in Polen. Band 1-4. Krakau.

Secondary literature (in distinct selection)

Aurenhammer, Hans H. (2009): Max Dvorak and the History of Medieval Art. In: Journal of Art Historiography (1), without pagination.

Bachmann-Medick, Doris (2006): Cultural Turns. Neuorientierungen in den Kulturwissenschaften. Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag.

Baigrie, Brain S. (Hg.) (1996): Picturing Knowledge. Historical and Philosophical Problems Concerning the Use of Art in Science. Toronto.

Bałus, Wojciech (2012): A marginalized tradition? Polish art history. In: Matthew Rampley und et al (Hg.): Art History and Visual Studies in Europe: Transnational Discourses and National Frameworks. Leiden, Boston, 439–449.

Bann, Stephan (2002): Der Reproduktionsstich als Übersetzung. In: Der Pantheos auf magischen Gemmen (Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus 6), 42–76.

Bartlova, Milena (2012): Art history in the Czech and Slowak republics: institutional frameworks, topics and loyalities. In: Matthew Rampley und et al (Hg.): Art History and Visual Studies in Europe: Transnational Discourses and National Frameworks. Leiden, Boston, 305–314.

Bartlova, Milena (2013): Continuity and discontinuity in the Czech legacy of the Vienna School of art history. In: Journal of Art Historiography (8), without pagination.

Benjamin, Walter (1972): Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers [1923]. In: Gesammelte Schriften, IV/1. Frankfurt am Main, S. 9-21.

Benjamin, Walter (2012 [1939]): Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Beyer, Andreas; Lohoff, Markus (Hg.) (2005): Bild und Erkenntnis. Formen und Funktionen des Bildes in Wissenschaft und Technik. München, Berlin.

Bickendorf, Gabriele (2006): Die Geschichte und ihre Bilder vom Mittelalter. Zur „longue durée“ visueller Überlieferung. In: Bernd Carqué, Daniela Mondini und Matthias Noell (Hg.): Visualisierung und Imagination. Materielle Relikte des Mittelalters in bildlichen Darstellungen der Neuzeit und Moderne. 2 Bände. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 103–152.

Bredekamp, Horst; Schneider, Pablo (Hg.) (2006): Visuelle Argumentationen. Die Mysterien der Repräsentation und die Berechenbarkeit der Welt. München.

Bredekamp, Horst; Werner, Gabriele (Hg.) (2013): Bildwelten des Wissens. Berlin.

Breidbach, Olaf (2005): Bilder des Wissens. Zur Kulturgeschichte der wissenschaftlichen Illustration. München.

Brzyski, Anna (2004): Constructing the Canon: The Album Polish Art and the Writing of Modernist Art History of Polish 19th-Century Painting, In: Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 1 (Spring 2004), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring04/284-constructing-thecanon-the-album-polish-art-and-the-writing-of-modernist-art-history-of-polish-19th-centurypainting. [26.03.2019].

Breuer, Constanze, Holtz, Bärbel, Kahl, Paul (Hg.) (2015): Die Musealisierung der Nation. Ein kulturpolitisches Gestaltungsmodell des 19. Jahrhunderts. Berlin, Boston.

Brückle, Wolfgang; Mariaux, Pierre Allain; Mondini, Daniela (Hg.) (2015). Musealisierung mittelalterlicher Kunst. Anlässe, Ansätze, Ansprüche. Berlin, München.

Burioni, Matteo (Hg.) (2016): Weltgeschichten der Architektur. Ursprünge, Narrative, Bilder 1700-2016. Passau: Dietmar Klinger Verlag (Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Kunstgeschichte in München, 40).

Carqué, Bernd; Mondini, Daniela; Noell, Matthias (Hg.) (2006): Visualisierung und Imagination. Materielle Relikte des Mittelalters in bildlichen Darstellungen der Neuzeit und Moderne. Max-Planck-Institut für Geschichte. 2 Bände. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag.

Chadraba, Rudolf et.al. (Hg.) (1986): Kapitoly z českého dĕjepisu umĕní I, II. Prag: Odeon.

Choay, Françoise (1992): L’Allégorie du patrimoine. Paris.

Choay, Françoise (1997): Das architektonische Erbe, eine Allegorie. Geschichte und Theorie der Baudenkmale. hg. von Ulrich Conrads und Peter Neitzke; übers. von Christian Voigt. Braunschweig, Wiesbaden.

Choay, Françoise (2009): Le patrimoine en questions. Anthologie pour un combat. Paris: Seuil.

Clausberg, Karl (1978): Naturhistorische Leitbilder der Kulturwissenschaften. Die Evolutionsparadigmen. In: Brix, Michael; Steinhauser, Monika (Hrsg.). Geschichte allein ist zeitgemäß. Historismus in Deutschland. Lahn-Gießen, 41–51.

Clausen, Christina (2016): Designing Cultural Memory: The Medieval Cathedral as a ‘Monument to History’ in Nineteenth-Century Painting, in: What’s the Use? Constellations of Art, History, and Knowledge, A Critical Reader, hrsg. von Nick Aikens, Thomas Lange, Jorinde Seijdel, Steven ten Thije, Amsterdam 2016, 92-110.

Cortjaens, Wolfgang; Heck, Karsten (Hg.) (2014): Stil-Linien diagrammatischer Kunstgeschichte. Berlin, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH (Transformationen des Visuellen hg. von Hubert Locher, 2).

Deneke, Bernward; Kahsnitz, Rainer (Hg.) (1977): Das kunst- und kulturgeschichtliche Museum im 19. Jahrhundert, München.

Dilly, Heinrich (1979): Kunstgeschichte als Institution : Studien zur Geschichte einer Disziplin. 1979 Heinrich Dilly. Frankfurt/Main.

Filipova, Marta (2008): The construction of national identity in the historiograhy of czech art. Dissertation.

Filipova, Marta (2013): Vincenc Kramar, ‘Obituary of Franz Wickhoff’. (Übersetzung). In: Journal of Art Historiography (8), without pagination.

Filipova, Marta (2013a): Between East and West: The Vienna School and the Idea of Czechoslovak Art. In: Journal of Art Historiography (8). without pagination.

Filipova, Marta (2013b): Vincenc Kramar, ‘Obituary of Franz Wickhoff’. (Übersetzung). In: Journal of Art Historiography (8), without pagination.

Gaberson, Eric (2013): Art History in the University II: Ernst Guhl. In: Journal of Art Historiography (7), without pagination.

Geimer, Peter (Hg.) (2002): Ordnungen der Sichtbarkeit. Fotografie in Wissenschaft, Kunst und Technologie. Frankfurt am Main.

Guile, Carolyn C. (2013): Winckelmann in Poland: An Eighteenth-Century Response to the ‘History of the Art of Antiquity’. In: Journal of Art Historiography (9). without pagination.

Haskell, Francis (1993): History and its images. Art and the interpretation of the past. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Heintz, Bettina; Huber, Jörg (Hg.) (2001): Mit dem Auge denken. Strategien der Sichtbarmachung in wissenschaftlichen und virtuellen Welten. Zürich, New York.

Heßler, Martina (Hg.) (2006): Konstruierte Sichtbarkeiten. Wissenschafts- und Technikbilder seit der Frühen Neuzeit. München.

Johns, Karl (2009): Moriz Thausing and the road towards objectivity in the history of art. In: Journal of Art Historiography (1), without pagination.

Jones, Caroline A.; Galison, Peter (Hg.) (1998): Picturing Science, Producing Art. York, London.

Kammel, Frank Matthias (Hg.) (2016): Leibniz und die Leichtigkeit des Denkens. Historische Modelle: Kunstwerke Medien Visionen. [Ausst.Kat.] Germanisches Nationalmuseum 30.06.2016-05.02.2017. Nürnberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums.

Krause, Katharina; Niehr, Klaus; Hanebutt-Benz, Eva-Maria (Hg.) (2005): Bilderlust und Lesefrüchte. Das illustrierte Kunstbuch von 1750 bis 1920. Leipzig: E. A. Seemann Verlag.

Kroupa, Jiři (1996): Školy dějin uměeni. Metodologie dějin uměni. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Fiozoficka fakulta.

Kuninska, Magdalena (2013): Marian Sokołowski: patriotism and the genesis of scientific art history in Poland. In: Journal of Art Historiography (8), without pagination.

Labuda, Adam (1996): Dzieje historii sztuki w Polsce : ksztatowanie sie instytucji naukowych w XIX i XX wieku. Poznan.

Latour, Bruno (1981). Visualization and cognition: thinking with eyes. In Kuklick, Henrika (ed.) Knowledge and Society. Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present, Jai Press vol. 6, 1-40.

Latour, Bruno (1996): Der Berliner Schlüssel. Erkundungen eines Liebhabers der Wissenschaften. aus dem Französischen von Gustav Roßler. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Locher, Hubert (2010): Kunstgeschichte als historische Theorie der Kunst 1750-1950. Genf.

Locher, Hubert (2012): The idea of the canon and canon formation in art history. In: Matthew Rampley und et al (Hg.): Art History and Visual Studies in Europe: Transnational Discourses and National Frameworks. Leiden, Boston, 29–40.

Makuljevic, Nenad (2013): The political reception of the Vienna School: Josef Strzygowski and Serbian art history. In: Journal of Art Historiography (8), without pagination.

Malinowski, Jerzy (Hg.) (2012): History of Art History in central, eastern and south-eastern Europe. Torun.

Małkiewicz, Adam (2005): Z dziejów polskiej historii sztuki: studia i szkice. Poznań.

Mersch, Dieter: Das Bild als Argument. Visualisierungsstrategien in den Naturwissenschaften. In: Ikonologie des Performativen, hg. v. Christoph Wulf u. Jörg Zifras, München. 2005.

Mondini, Daniela (2005): Mittelalter im Bild. Séroux d’Agincourt und die Kunsthistoriographie um 1800. Zürich: Zürich InterPublisher (ZIP) (Züricher Schriften zur Kunst-, Architektur- und Kulturgeschichte, 4).

Mondini, Daniela (2014): ‚Kunstgeschichte in Bildern‘. Visuelle Didaktik und operative Schautafeln in Séroux d’Agincourts Histoire de l’Art par les monumens ([1810-]1823). In: Wolfgang Cortjaens und Karsten Heck (Hg.): Stil-Linien diagrammatischer Kunstgeschichte. Berlin, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH (Transformationen des Visuellen hg. von Hubert Locher, 2), 80–95.

Muthesius, Stefan (2013): The Cracow school of modern art history: the creation of a method and an institution 1850-1880. In: Journal of Art Historiography (8). without pagination.

Narodní Technické Muzeum (Hg.) (2015): Katalog expozice. Architektura, stavitelství a design. Prag.

Niehr, Klaus (1999): Gotikbilder-Gotiktheorien. Studien zur Wahrnehmung und Erforschung mittelalterlicher Architektur in Deutschland zwischen ca. 1750 und 1850. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag.

Niehr, Klaus (1999): Gotikbilder-Gotiktheorien. Studien zur Wahrnehmung und Erforschung mittelalterlicher Architektur in Deutschland zwischen ca. 1750 und 1850. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag

Oechslin, Werner (2011): Architekturmodell. “idea materialis‘. In: Wolfgang Sonne (Hg.): Die Medien der Architektur. München, Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH, 131–155.

Passini, Michela (2012): La fabrique de l’art national: le nationalisme et les origines de l’histoire de l’art en France et en Allemagne, 1870 – 1933. Paris.

Philipp, Klaus Jan (1998): Gänsemarsch der Stile. Skizzen zur Geschichte der Architekturgeschichtsschreibung. Stuttgart.

Philipp, Klaus Jan (2006): Mittelalterliche Architektur in den illustrierten ‚Architekturgeschichten‘ des 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhunderts. In: Craqué, Mondini, Noell (Hg.): Visualisierung und Imagination, 378–416.

Polanowska, Jolanta (1995): Historiografia sztuki polskiej w latach 1832 – 1863 na ziemiach centralnych i wschodnich dawnej rzeczypospolitej. F. M. Sobieszczansi; J. I. Kraszewski; E. Rastawiecki; A. Przezdziecki. Warschau.

Pullins, David (2017): The individual’s triumph: the eigteenth-century consolidation of authorship and art historiography. In: Journal of Art Historiography (16), without pagination.

Rampley, Matthew (2012a): Heritage, ideology, and identity in Central and Eastern Europe. contested pasts, contested presents. 1. publ. Woodbridge: Boydell Press (The heritage matters series, 6).

Rampley, Matthew (2013): The Vienna School of Art History: Empire and the Politics of Scholarship, 1847–1918. Pennsylvania.

Rampley, Matthew; et al (Hg.) (2012a): Art History and Visual Studies in Europe: Transnational Discourses and National Frameworks. Leiden, Boston.

Rampley, Matthew (Hg.) (2012b): Heritage, Ideology and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe. Contested Pasts, Contested Presents. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

Recht, Roland (1999, 2008): Penser le patrimoine: mise en scène et mise en ordre de l’art. Paris.

Reuther, Hans; Berckenhagen, Ekhart (1994): Deutsche Architekturmodelle. Projekthilfe zwischen 1500 und 1900. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaften.

Ruhl, Cartsen; Dähne, Chris (2015): Architektur ausstellen: zur mobilen Anordnung des Immobilen. Berlin.

Sachsse, Rolf (1984): Photographie als Medium der Architekturinterpretation. München.

Sonne, Wolfgang (Hg.) (2011): Die Medien der Architektur. München, Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH.

Thome, Markus (2015): Narrativer Überbau. Museumsarchitektur und Raumgestaltungen in Formen einer nationalen Baukunst. In: Breuer, Constanze; Holtz, Bärbel; Kahl, Paul (Hrsg.) Die Musealisierung der Nation. Ein kulturpolitisches Gestaltungsmodell des 19. Jahrhunderts. Berlin, Boston. pp. 201–236.

Tietenberg, Anette (Hg.) (1999): Das Kunstwerk als Geschichtsdokument. München.

Venuti, Lawrence (1995): Translator’s Invisibility. A history of translation. London, New York: Routledge.

Vybiral, Jindrich (2006): What is ‘Czech’ in Art in Bohemia? Alfred Woltmann and defensice mechanisms of Czech artistic historiography. In: Kunstchronik. Monatszeitschrift für Kunstwissenschaft, Museumswesen und Denkmalpflege 59 (1), 1–7.

Wittlich, Petr (1992): Český dějepis uměni. In: Literatura k dějinám uměni přehled. Prag: Karolinum.