Shaping & Establishing a Canon of National Monuments: Jan Sas Zubrzycki’s „Treasury of Architecture in Poland“ (1907-1916)

The institutionalisation and emancipation of art history in Europe was driven and shaped by the search for national identity in the 19th century. While other European countries enjoyed political sovereignty, the lack of national independence as well as the differing levels of foreign cultural dominion in the Central European territories of Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire lead to multifaceted approaches to art history. Conveying a specific national canon of literature, art or architecture was fundamental in the process of preserving and constructing national identity. Since every science is necessarily prompted to use suitable representations to approach the world, this art historical canon materialised in numerous volumes and scientific articles. The images created for this specific purpose have a certain autonomy in the discourse – thus, they shaped and established the canon of art history and history of architecture in particular.

Unfortunately, this broader European context is rarely a subject of ‘canonical’ (meaning common) art historical research; therefore, I aim to complement the discussion about canon by widening the frame of investigation to Central European art historical practice in the beginning of the 20th century.

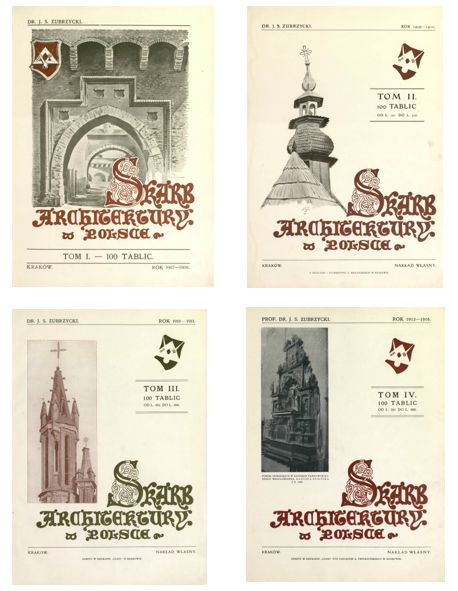

Consequently, I chose “Skarb architektury w Polsce” (Treasury of Architecture in Poland, 1907-1916) by Jan Sas Zubrzycki as a starting point for the planned contribution. Within its four published volumes a visual canon of Polish architectural history is constructed. To mediate his interpretation of the Polish history of architecture, Zubrzycki uses his own drawings, photographs and reproductions of illustrations from other publications or directly of art works. The heterogeneous visual material in “Treasury of Architecture in Poland” not only illustrates the multimediality of art historical practice at the time and the coeval search for adequate visualisations methods, but also characterises the pursuit of scientific (and of course also political) independence by writing a Polish history of architecture emancipated from the German-speaking and Western-focused discourse.

Zubrzycki’s approach clearly differs from the modernist solutions of his European colleagues (i.a. the Vienna School of art history namely Alois Riegl, Franz Wickhoff and Max Dvořak or German scholars like Georg Dehio or Anton Springer) as well as from his contemporaries of the Krakow school of art history, concentrating on more objective and rigorous methods to depict and analyse architecture for art historical research. Zubrzycki not only uses unusual illustrations to stimulate the imagination of the percipient but also suggests a national-romantic understanding of art history, strongly shaped by the concept of fundamental difference between the Slavic culture and those of the other European nations.

As part of my contribution to this colloquium, I focus on the following questions: How do the images in these volumes shape the presented canon of architectural monuments, considering the visualisation strategies, printing techniques and the underlying line of arguments? Ensuing the problem of reproduction, authorship and the market but also the construction of national heritage in Poland – therefore the establishing of a specific canon.

Accordingly, I will briefly present a characteristic selection of images from this compendium to answer the above-formulated questions. The comparison of the results with the broader context of the coeval European art-historical discourse bears the opportunity to discuss the role of images in the formation of an architectural canon and the writing of an art history. This confrontation opens the discussion for related and important general questions: Why were visual approaches like Zubrzycki’s not successful in art-historical discourses? Which are the current and continuous expectations of art-historical images? Who shapes this visual canon art historians rely on in their research? And most importantly, how can this knowledge be determined and visualised in the future?

A closer look at this small but divergent aspect of the complex, pan-European context of art history illuminates the reciprocal relation between the images and the formation of an art historical canon in the beginning of the 20th century – leaving its traces until today.

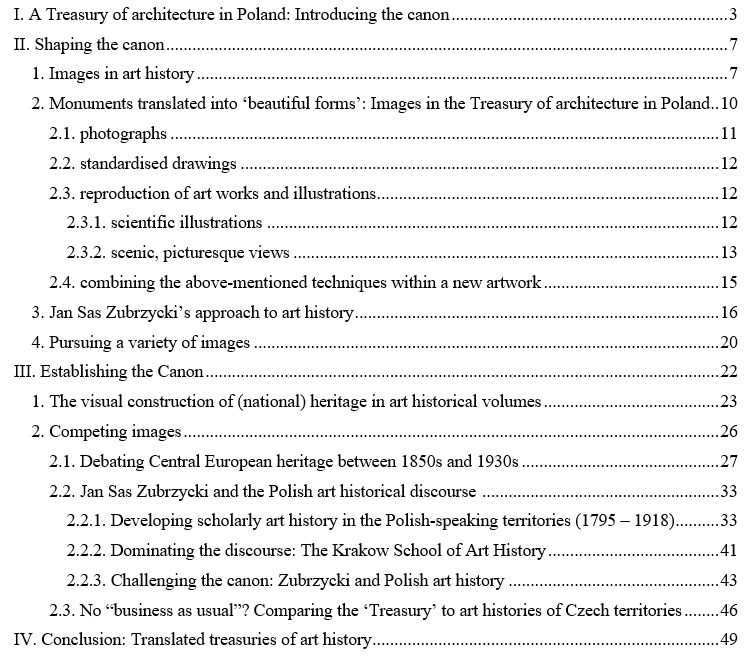

Content

Conclusion: Translated treasuries of art history

This text aimed to explore the processes of shaping and establishing visual canons. It further pursued the question how visual working objects construct (national) heritage on a microlevel through analysing Jan Sas Zubrzycki’s “Treasury of Architecture in Poland”.

Visual canons like the ones examined above are shaped according to art historical preferences and theoretical approaches to art itself. Hence, Jan Sas Zubrzycki’s canon of Polish architecture consists especially of medieval monuments, representing his research focus and his idea of national styles giving prominence to the Vistula and the Sigmund Style. Those scholarly interests further are persecuted in gathering available material; meaning on the one hand, images of monuments in the circumcircles of his own life (see ill. 21) and on the other hand, material that was already published or produced for other purposes, but fit his own objective well, like the reproductions from journals or various types of photographs. In analysing the drawings by Józef Smoliński, Zubrzycki’s appreciation for artistic depictions has become visible. Despite the scholarly approach of his work, he accepts artistic values within the imagery provided. The additional overlap with popular culture (with reproductions from journals) provide an alternate visual approach to the comparison of the objects. Although the practice of visual comparison then already as common in art history as it is today, Zubrzycki does not aim to engage the viewer in an objective analysis, but to stimulate his imagination and emotion. This approach corresponds to his theoretical understanding of architecture as symbols with exoteric and more importantly esoteric meaning. The latter comprises the ‘national spirit’ and evokes emotions in the viewer – who reciprocally can identify this spirit. The imagery in the “Treasury of Architecture in Poland” includes various visual approaches to the monument itself, facilitating a pliable reception. This method is comparable to artistic translation, that not only aiming to capture the original but transfers it to a new (material, ideological, political, historical etc.) context. In doing so, it enables the viewer to identify the object, and moreover to reach additional knowledge i.e. connections to other works, stylistic peculiarities, or a certain rating of information that is particularly emphasised in the translation. Walther Benjamin (1923) characterises artistic translation as an ongoing process in which the original in its different translations takes on additional meaning.[1] He further argues, that the ‘essence’ of the original will be revealed as an unattainable result of this process.[2]

Summarising the results of the analysis of content and visual form of Zubryzcki’s shaping of an architectural canon, it can be stated that the “Treasury of Architecture in Poland” represents a personally, politically, socially, and art historically limited canon of (national) monuments, visually translated to directly engage the viewer in the process of identifying (national) art and its characteristics.

The published plates represent a heterogenous mixture of images, which Dvořak surely would have criticised as an unfavourable “mishmash of realia”[3]. Although there were other attempts to describe, catalogue, and identify (national) art in topographies, monographs, and art histories, Zubrzycki does not refer to them regarding their argumentation in his volumes. However, he does use several reproduced plates from German-speaking and one Polish-speaking volume. But even though he lived and worked in Austro-Hungaria Zubrzycki ignores the findings, publications and discourses present. Nonetheless Zubrzycki is explicitly involved in the coeval art historical discourse. He challenged and opposed the approaches of his contemporaries of the Cracow School of Art History and respectivly his collegues in Vienna. Zubrzycki’s approach is considered to be conservative and national-romantic. Anyhow, he managed to establish a canon of (national) architecture, that was perceived mostly regardless of its theoretical context. In comparison with the Austrian and the Bohemian topographies the blending between national-romantic transfiguration and scholarly work in the “Treasury of Architecture in Poland” is obvious.

Therefore I want to argue that the fact-oriented publications of his contemporaries have lost their validity with increasing knowledge of art history. The visual images within the texts have lost their power to communicate because they were closely linked to the texts surrounding them. Zubrzycki’s „Treasury of Architecture in Poland“, on the other hand, gained general importance in constructing national monuments. The assumed ability of the pictures to evoke memories and relate feelings justifies its timeless usability. Regardless of the ideological and scientific interests pursued by its editor, the subject matter, namely national heritage, remained the same, despite Zubrzycki’s publication simultaneously failing to meet its scientific objective – if present at all. The art historical working objects are instead places of remembrance. I conclude that the long reception and meaning of the visual ‚treasury‘ is based on its variety of artistic translation: consequently the images could continue to be used as long as their translation of cultural heritage was valid, which was valid far longer than the scientific approach represented in it.

“By studying it [art history], the art historian produces the heritage and prepares its public use, in which he participates, as sometimes to its instrumentalisation.”[4]

According to Michaela Passini, art historians are closely involved in the construction of (national) heritage and shape the public’s perception of it.[5] Art history is furthermore closely related to its protagonists and their respective social, political, historical, and cultural background.[6] Klaus Jan Philipp (1998) accordingly determines:

“Every time has its contemporary view of historical architecture, and something of the current architectural scene will always be reflected in the books on the history of construction. However, as easy as this judgment can be in retrospect, it is difficult to admit this condition to yourself. Because one strives for objectivity, which should give one’s own analysis and interpretation a timeless validity. However, the half-life of science believed objectively shortens progressively with the political and architectural development, so that after the reunion of Germany or after the dissolution of the ‚ Ostblocks‘ also a general architectural history of Germany or Europe would have to be rewritten.”[7]

Concurrently, there will always be a need for art historical working objects, meaning visual depictions of original monuments, artefacts, and artworks, which cannot be directly viewed due to their geographical location, their condition, their present lack or material disposition. Georg Dehio (1907) formulated the well-known problem perhaps first, but certainly not last:

“At least the external acquaintance with works of art, old and new, is more widespread than ever in the generation living today. It is modern technology that has created completely new conditions for our culture. […] Poetry can be left unread; Not seeing architectures, sculptures, pictures and their replicas is almost impossible. Today’s man, whether he likes it or not, is under a flood of impressions of this kind, and his greatest concern should be to put his mind in order in this many, this multitude, to some extent.“[8]

He concludes that the book market is meeting these demands, however, a national (German) art history seems lacking.[9] Dehio’s statement emphasises the role of manuals and art history publications in this context, as Hubert Locher (2001) does.[10] Locher further argues that manuals in particular have been and still are mediators between historical science and art production, between professional scholars and laymen.[11]

In

short, it is crucial to examine the process of canon formation and at the same

time not lose sight of current art historical needs and contexts. On the

contrary, in times of digital media it is all the more important to deal with

the translation possibilities of art and the knowledge about it. The question arises

how, when, and where art had to be translated historically and will be so in

the future and for what purpose. The example of Zubrzycki’s ‚Treasury‘ and the comprehensive

studies of other art historians show that on the one hand, images are closely

interwoven with the construction of cultural heritage and on the other hand,

gain autonomy in the (art historical) discourse. At the same time, more

flexible translations make it possible to align and update their meaning, as

was the case with the images of Polish cultural heritage through Jan Sas

Zubrzycki.

[1] Benjamin, Walter. “Die Aufgabe Des Übersetzers [1923].” In Gesammelte Schriften. IV/1, pp. 9-21. Frankfurt am Main, 1972.

[2] Benjamin, Walter. “Die Aufgabe Des Übersetzers [1923].” In Gesammelte Schriften. IV/1, pp. 9-21. Frankfurt am Main, 1972. Seite.

[3] Dvořák, “Einleitung,” in Österreichische Kunsttopographie, 1:xix., cited after Rampley, Matthew (2013): The Vienna School of Art History: Empire and the Politics of Scholarship, 1847–1918. Pennsylvania, 191.

[4] Passini, Michaela. La Fabrique De L’art National: Le Nationalisme Et Les Origines De L’histoire De L’art En France Et En Allemagne 1870-1933. Passage/Passagen. Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte Volume 43. Paris: Edition de la Maison des science de l’homme, 2012, 254.

[5] Passini, Michaela. La Fabrique De L’art National: Le Nationalisme Et Les Origines De L’histoire De L’art En France Et En Allemagne 1870-1933. Passage/Passagen. Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte Volume 43. Paris: Edition de la Maison des science de l’homme, 2012, 253-254.

[6] Passini, Michaela. La Fabrique De L’art National: Le Nationalisme Et Les Origines De L’histoire De L’art En France Et En Allemagne 1870-1933. Passage/Passagen. Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte Volume 43. Paris: Edition de la Maison des science de l’homme, 2012, 253-254.

[7] Philipp, Klaus J. Gänsemarsch Der Stile: Skizzen Zur Geschichte Der Architekturgeschichtsschreibung. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH, 1998, 46.

[8] Dehio, Deutsche Kunstgeschichte und deutsche Geschichte; in: ders.: Kunsthistorische Aufsätze, München/Berlin 1914. S.61-74. hier 64 – Beitrag erschien zuerst in: Historische Zeitschrift 100, 1907).

[9] Dehio, Deutsche Kunstgeschichte und deutsche Geschichte; in: ders.: Kunsthistorische Aufsätze, München/Berlin 1914. S.61-74. hier 64 – Beitrag erschien zuerst in: Historische Zeitschrift 100, 1907)

[10] Locher, Hubert. Kunstgeschichte Als Historische Theorie Der Kunst 1750-1950. München: Wilhelm Fink, 2001, 211.

[11] Locher, Hubert. Kunstgeschichte Als Historische Theorie Der Kunst 1750-1950. München: Wilhelm Fink, 2001, 211.